From October 2020 through May 2021, an eighteenth-century painting on display at the Yale Center for British Art was replaced by Titus Kaphar’s Enough About You (2016). What follows is an explanation of why this change was made and a description of the ongoing research into the picture previously titled Elihu Yale; William Cavendish, the second Duke of Devonshire; Lord James Cavendish; Mr. Tunstal; and an Enslaved Servant, referred to here by its accession number, B1970.1.

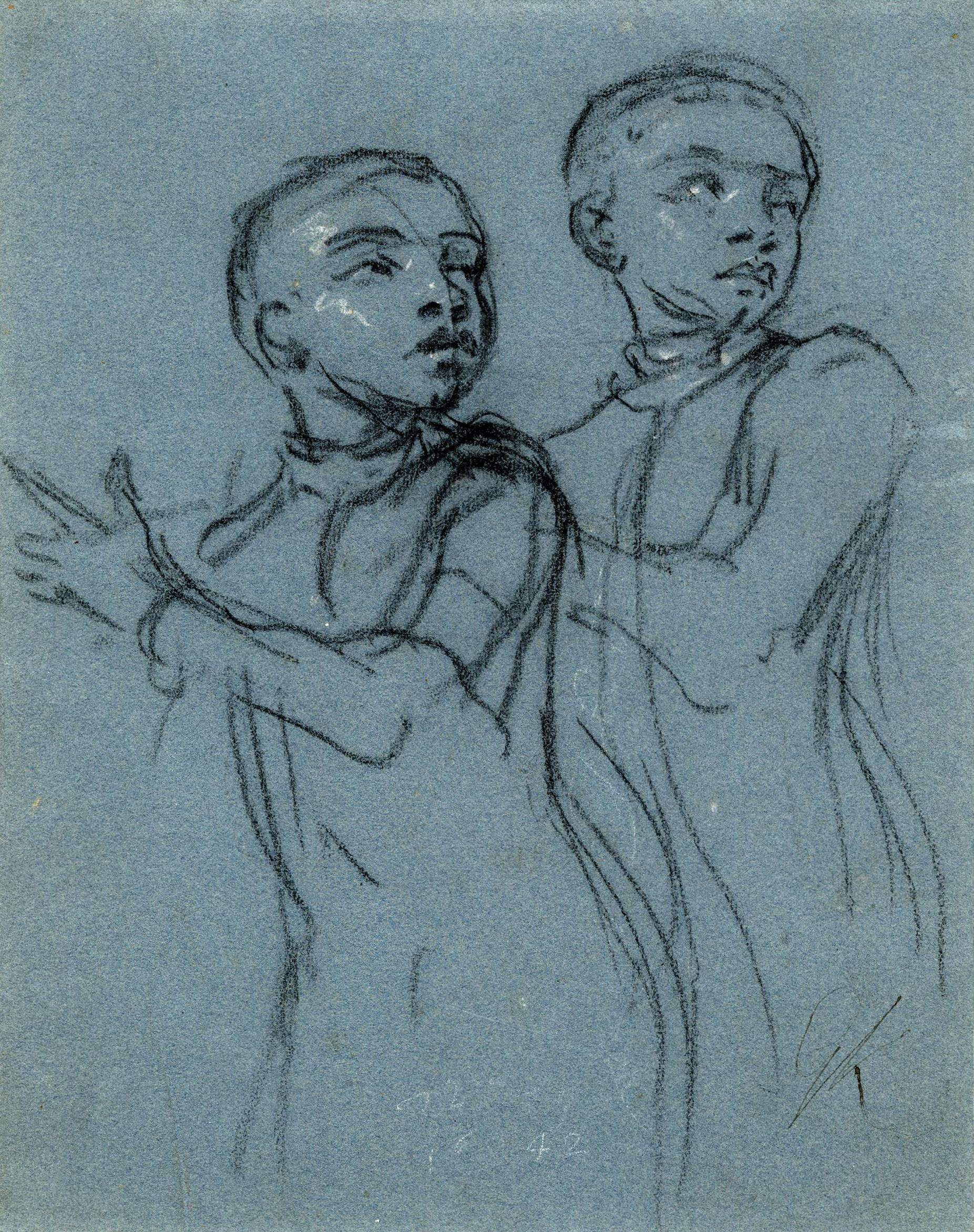

While the children in the background are shown freely at play, the child in the foreground is shown at work. Like many other depictions of people of African descent in British portraits from this period, the boy’s identity has been largely ignored. The collar on his neck is of a type seen in at least fifty other paintings made in Britain between 1660 and 1760. Even though the identity of figures of African descent in these paintings are often unknown, for the most part the portraits depict individuals, taken from life, such as these studies made by the court painter Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723).

Sir Godfrey Kneller, A black page; two studies in the same pose, one slighter than the other, three quarter length, standing, half-l, looking back over the left shoulder pointing upwards with left hand, black chalk, touched with white, on blue-gray paper, 1685–1690, British Museum 1888,0719.77

These portraits provide a stark reminder of Britain’s entrenchment in the transatlantic slave trade, which by the beginning of the nineteenth century had brought more than two and a half million people from the west coast of Africa to be sold into chattel slavery. The paintings also point specifically to the invidious practice in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries of bringing children (mainly boys under ten years old) to Britain to work as domestic servants in elite households. The enslaved child depicted in B1970.1 would have served as a “page,” that is a child attendant as part of the household of one of the seated men.

Chattel slavery was ostensibly unlawful within Britain’s shoreline. But as B1970.1 shows, this did not stop thousands of Black children and adults from being brought to Britain over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in an ill-defined but often violently enforced state of what historians have characterized as “slavish servitude.” Having already suffered separation from family and often multiple episodes of displacement, there was the constant threat of being resold into slavery abroad by either kidnappers or those that claimed “ownership” over them in Britain. Collars made of silver, steel, or brass, of the type seen in B1970.1 were not used to tether the wearer to other shackles but were impossible to divest from the body and served to deter escape. It is this, and other dehumanizing actions, that Titus Kaphar subverts in his painting.

Titus Kaphar, Enough About You (detail), 2016, oil on canvas with an antique frame, on loan from the Collection of Arthur Lewis and Hau Nguyen, Courtesy of the artist, photo by Richard Caspole

By literally reframing B1970.1 and depicting the child as a singular individual, defiant and rid of his collar, Kaphar’s work demonstrates how historic depictions of people of African descent in the Black Atlantic intersect with contemporary issues of inequality and the continued lack of representation of Black people today. In his own words, Kaphar “wanted to find a way to imagine a life for this young man that the historical painting had never made space for in the composition: his desires, dreams, family, thoughts, hopes. Those things were never subjects that the original artist wanted the viewer to contemplate.” Enough About You creates a space to imagine a life for this child. It also encourages a reckoning with the historic painting from which it draws.

It is now half a century since B1970.1 was acquired by a gift from the eleventh Duke of Devonshire (1920–2004), Andrew Cavendish, to Paul Mellon on behalf of Yale University. The acquisition was championed by the first director of the Center, Jules Prown, who argued that the picture depicted a “powerful likeness” of Elihu Yale and would serve as an “important exhibit at the Mellon Center, underlining the ties between England and America that have been so important for America and her institutions.”

The painting was the first artwork to formally enter the collection of the Yale Center for British Art, in 1970, several years before the museum opened its doors to the public in 1977. Initially the picture was kept in storage, only making a brief appearance in the 1981 exhibition The Conversation Piece: Arthur Devis and His Contemporaries before being hung in the dining hall of a residential college. In 2014, it was the starting point for the exhibition Figures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain. Upon the closure of that exhibition, it was included in the reinstallation of the Center’s collection, which opened in 2016.

In September 2020, Director Courtney J. Martin formed a curatorial team to explore and better understand the history of this painting: how it had come to Yale, and the various ways it has been thought about and discussed in the past, in order to make transparent its complex history.

This year, for the first time in its history, the painting has been subject to a thorough technical study, bringing to light new information that corrects longstanding assumptions about what the painting depicts and has implications for our understanding of the child’s biography.

B1970.1 and Yale University Art Gallery's 1960.51 in the Painting Conservation Studio at the Yale Center for British Art, photo by Jessica David

A small-scale version of B1970.1, painted on copper, was acquired by the Yale University Art Gallery in 1960. Despite the dramatic difference in size, the copper painting is faithful to the larger work on canvas and used a similar system of paint application and a seemingly identical palette.

Unknown artist, Elihu Yale seated at table with the Second Duke of Devonshire and Lord James Cavendish, ca. 1708, oil on copper, Transfer from the Yale University Library, Gift of Mrs. Arthur W. Butler, 1960.51

The painting has long been thought to mark the successful negotiation of the marriage of Anne (1687–1734), daughter of Elihu Yale, and Lord James Cavendish (aft. 1673–1751), younger brother of William, second Duke of Devonshire (1672–1729). Based entirely upon suppositions made by the then owner, this interpretation first appeared in an article published in an antiquarian journal in 1862 about a country house in Derbyshire, England, called Staveley Hall, home of Lord James Cavendish and Anne Yale. After James Cavendish died in 1751, his family permitted his friend the Rector James Gisborne (1688–1759) to live at Staveley. It was through Gisborne that the painting was eventually inherited by Francis Ernest Gisborne Bagshawe (1893–1985) of Ford Hall, Derbyshire. In 1941, alarmed at the thought of “all these old things going to America,” Bagshawe decided to sell B1970.1 to his Derbyshire neighbor Edward Cavendish, tenth Duke of Devonshire (1895–1950). What Bagshawe could not have anticipated is that less than thirty years later the next Duke of Devonshire would give the painting to his friend Paul Mellon for the Yale Center for British Art.

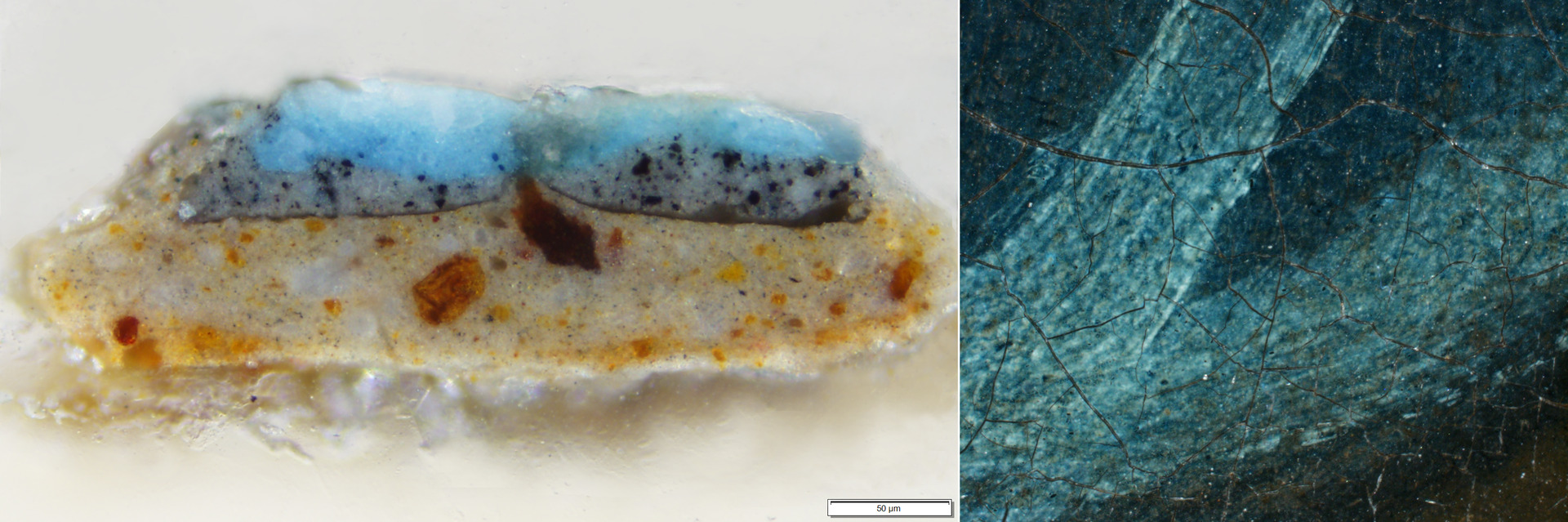

Left: Cross section taken from B1970.1 where analysis has identified the pigment Prussian Blue. Right: Microphotograph showing the area of the blue coat in the painting from which the sample was taken. Photos by Jessica David

Analysis undertaken in collaboration with Yale’s Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage has identified the presence of the pigment Prussian Blue, which was used as a glaze for the blue coat of the man in the foreground. This is significant because Prussian Blue was not in use in Britain until 1719, when it was brought from mainland Europe by the French painter Antoine Watteau (1684–1721). This makes the 1708 date long given to B1970.1 impossible and puts in doubt any association with Anne Yale’s marriage contract. There are other factors that cast doubt on the date. Lord James Cavendish wears a “campaign style” wig tied at one end, which only became fashionable during the subsequent decade; moreover, the absence of paper, ink, pen, or any activity beyond the taking of tobacco and wine, does not support the idea that this painting records a marriage contract.

We can be confident about the identities of Lord James Cavendish and Elihu Yale in B1970.1 because their likenesses match those in other portraits. The identities of the other sitters are less secure. The longstanding identification of the seated man wearing a blue coat as William Cavendish, second Duke of Devonshire, hinges entirely upon a nineteenth-century observation of a familial resemblance between the two men sitting on either side of Elihu Yale, yet comparison with other securely identified portraits of Devonshire does not bear this out. Who then could he be?

Unknown artist, The North Family at Glemham, 1715–16, oil on copper, Ipswich Borough Council Museums and Galleries, Suffolk, UK

Based on comparisons with other portraits, the most likely answer is that this is Dudley North (1684–1730) of Glemham Hall, Suffolk, who in 1706 had married Yale’s eldest daughter, Catherine (1684–1715). They had three children: Dudley (1707–1764), Anne (1708–1789), and Mary (1715–1770). The son of a wealthy merchant, North was educated at Cambridge and was a member of the House of Commons. This would make the two men sitting on either side of Elihu Yale his sons-in-law, or as he would have described them: “his sons.” In turn, the children in the background are almost certainly Yale’s grandchildren: Dudley, Anne, and Mary North; and William (1711–1751) and Elizabeth Cavendish (1712–1779). The identity of the violinist remains a mystery.

The nineteenth-century identification of the young man who holds a book and rests his arm on the back of Elihu Yale’s chair as the lawyer “Mr. Tunstal” is difficult to reconcile with the age of this sitter, who cannot be much older than eighteen. There was a James Tunstall, an attorney of Richmond, Yorkshire, whose son was a clergyman, but neither father (too old) nor son (too young) were the right age in the first decades of the eighteenth century to be the youth depicted in this painting. Whatever the case, this is not a member of the Tunstall family. What seems more likely is that this young man is David Yale (1699–1730), the son of Elihu Yale’s cousin John Yale (1646–1711) of New Haven, Connecticut.

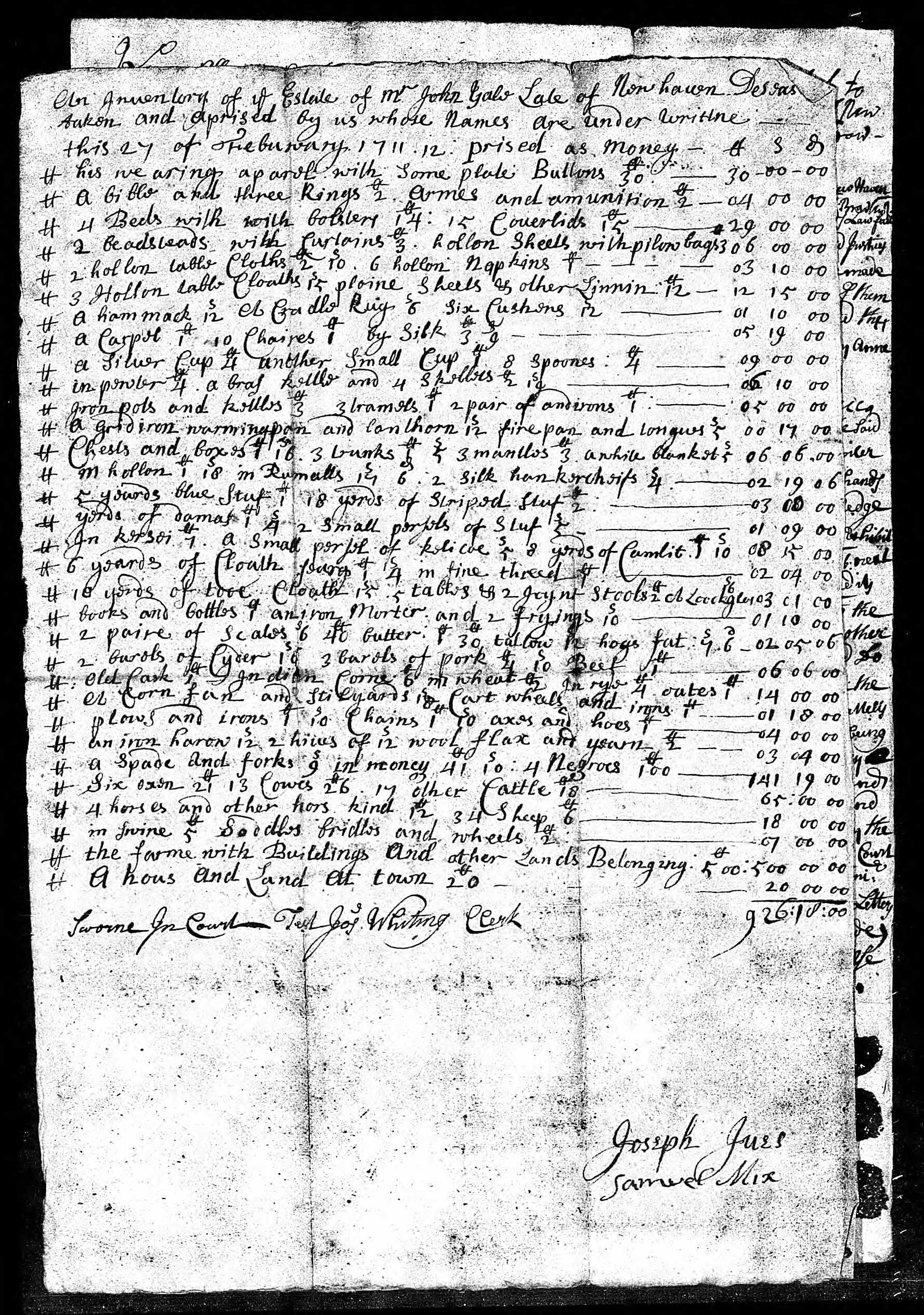

"An Inventory of ye Estate of Mr John Yale of New Haven Deceased," February 1712, Connecticut State Library, Hartford, Connecticut, Probate Packets, Woolsey, John-Z, Misc, 1683–1880

John Yale was an extensive planter in New Haven who died when his son David was still young. The probate inventory of John Yale’s estate of 1712 reveals the family’s wealth. It lists not only luxurious household items, but also four enslaved African Americans “valued” at £100 or £25 each, representing over 10 percent of the value of the total estate. Even prior to his father’s death, David Yale was being groomed as Elihu Yale’s heir. A letter of 1711 from Jeremy Dummer (1681–1739) in London to the Reverend James Pierpont (1659–1714) of New Haven gave notice that: “Here is Mr. Yale, formerly Governor of Fort George in the Indies, who has got a prodigious estate, and now by Mr. Dixwell sends for a relation of his from Connecticut to make him his heir, having no son.” A double portrait of Elihu and David Yale, once at the North family’s home of Glemham Hall, Suffolk, but now at Yale University, is probably the painting mentioned in a letter of 1719, which describes it as an intended gift from Yale to the university, but it was never sent.

Attributed to James Worsdale, Elihu Yale with a Young man, 1714, oil on canvas, Elizabethan Club, Yale University

A comparison between David Yale in the double portrait illustrated above and the young man with the long oval face, full lips, prominent forehead, wide-set eyes, and long nose with a pointed tip in B1970.1 suggests strongly that it is the same young man depicted in these two paintings. It seems that David spent most of the 1710s in London and Wales with Elihu Yale. In 1719 he was admitted at the Inner Temple, one of the Inns of Court in London, and later the same year, aged eighteen, became a Fellow Commoner at Pembroke College, Cambridge.

Close study of B1970.1 has revealed that the young man identified here as David Yale was not part of the original composition but was added during the process of painting. We know this because his face and upper body are painted thickly on top of a layer of green paint laid down to depict the trees in the background. This layer of green paint had been allowed to dry before his figure was added.

Details of the green paint layer seen through drying cracks in David Yale’s face in B1970.1, photos by Jessica David

Given that Elihu Yale’s family was split across a number of counties and was rarely, if ever, together in one place, it seems that B1970.1 was an attempt to unite them on canvas so as to illustrate, on a grand scale, that his legacy was secure. Only a decade earlier, an East India Company official, writing from London to Elihu Yale’s successors as governor of Fort St. George, had given a dismal description of Yale “in his choultry hid in tobacco smoke with a greasy nightgown, and a ___ in a chair by him, a scurvy painter or two drawing him in for some choice piece in which he is become a very great virtuoso or a bubble. Sometime you find him sett between two diamond cutters, sometimes a broker or two about matching his daughters; and often with the ingenious Sir Charles Cotterell of the Ceremonies.” This seedy scene casts Yale as a rich, aspirational, and gullible retiree, duped into buying bad art from disreputable painters and fixated on securing his legacy through his daughters’ marriages. The sneering mention of the “choultry” references the objects that Yale brought back from India and furnishings, such as tapestries woven for him in London, that drew inspiration from Mughal textiles. After Yale’s death these came to Glemham and were subsequently acquired by the university—the first in a succession of objects seized upon by Yale University alums as the contents of Glemham were auctioned in the 1920s.

Of the sales of Yale’s own collection, published in six auction catalogues, only a handful of paintings were described in sufficient detail to be identified today. Of the numerous portraits listed, only one lot names a contemporary sitter, making it impossible to know whether B1970.1 or the version on copper were in Yale’s collection at the time of his death. From what can be gleaned from the auction catalogues, Yale’s collecting practice was typical of his day. He followed a propensity among British collectors to acquire highly finished paintings on a small scale, particularly those made by Dutch artists who had moved to London. One of these painters is John Verelst (ca. 1675–1734), a strong candidate for the artist of B1970.1 and the version on copper. Born into a family of still-life painters who moved to London from the Netherlands during the second half of the seventeenth century, Verelst worked as both a portraitist and a dealer of pictures from London. Crucially, he also worked in oil on copper—a technique acquired from his father, Herman. The Verelst family were certainly known to Elihu Yale, who at the time of his death owned at least eight paintings ascribed to the Verelsts.

Composite image of details from B1970.1 and details of two signed and dated works by John Verelst. From left to right: Elihu Yale, photo by Jessica David; John Verelst, Unknown Man (detail), signed and dated 1717, photo by Roy Precious; John Verelst, Unknown Man, signed and dated 1719, photo courtesy of the Frick Collection Photo Archive

John Verelst’s earliest paintings date from 1697, which suggest he may have begun running his father’s studio at that time. A popular painter in his day, John Verelst is today best known for his portraits of the “Four Indian Kings” commissioned by Queen Anne for Kensington Palace and now at the National Archives of Canada. Stylistically, his signed portraits provide compelling comparisons with the portraits in B1970.1.

Attributed to John Verelst, Elihu Yale with Members of his Family and an Enslaved Child, ca. 1719, oil on canvas, Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Andrew Cavendish, eleventh Duke of Devonshire, B1970.1

What does this new information mean for our understanding of the identity and life of the enslaved child? The date of the painting can now be said to fall between 1719 (when Prussian Blue was introduced into Britain) and 1721 (when Yale died). Given the youthful appearance of the child in B1970.1, this suggests a birth date of around 1712. It is likely that he was brought to England at around the age of five and presumably had been in the household of one of the seated men for three or four years. It is still not known which household this was: a survey of the parish registers for the area in and around Yale’s London home in Queen Square reveals a small but significant number of individuals of African descent in Bloomsbury in the early eighteenth century, but there is no record in these registers that can be associated with the child in the painting. However, the survival of the accounts of Dudley North for this period do provide an avenue for further research. What can be said is that in around 1720, this child’s likeness was taken by a London-based artist, most likely from a dynasty of artists who, on occasion, incorporated figures of African heritage into their still-life compositions but were trained principally in the depiction of Caucasian skin tones. Despite the limitations of Verelst’s training and ability, his two paintings—one on canvas, one on copper—are currently the only record of the child’s existence and today provide the principal means by which the child’s identity might still be recovered.

This project was researched, written, and produced by the Elihu Yale Portrait Research Team formed by Director Courtney J. Martin at the Yale Center for British Art: Eric James, Software Engineer; Abigail Lamphier, Senior Curatorial Assistant; Lori Misura, Senior Library Assistant; David K. Thompson, Coordinator of Cataloguing; and Edward Town, Head of Collections Information and Access.

Background Images (top to bottom)

Titus Kaphar's Enough About You (2016) installed at the Yale Center for British Art, October 2020, on loan from the Collection of Arthur Lewis and Hau Nguyen, Courtesy of the artist, photo by Richard Caspole

Installation of Titus Kaphar's Enough About You (2016) at the Yale Center for British Art, October 2020, on loan from the Collection of Arthur Lewis and Hau Nguyen, Courtesy of the artist, photo by Richard Caspole

Enoch Seeman the Younger, Portrait of Gov. Elihu Yale (1648/49–1721) (detail), 1717, oil on canvas, Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Dudley Long North, M.P., 1789.1

John Obrisset, Elihu Yale Snuffbox (detail), ca. 1710–20, silver and tortoiseshell, Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Ezra Stiles, 1788.1

Attributed to John Verelst, Elihu Yale with Members of his Family and an Enslaved Child (detail), ca. 1719, oil on canvas, Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Andrew Cavendish, eleventh Duke of Devonshire, B1970.1

John Vanderbank the Elder, The Concert (detail), ca. 1700, wool and silk, Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Edward S. Harkness, BA 1897, 1926.30