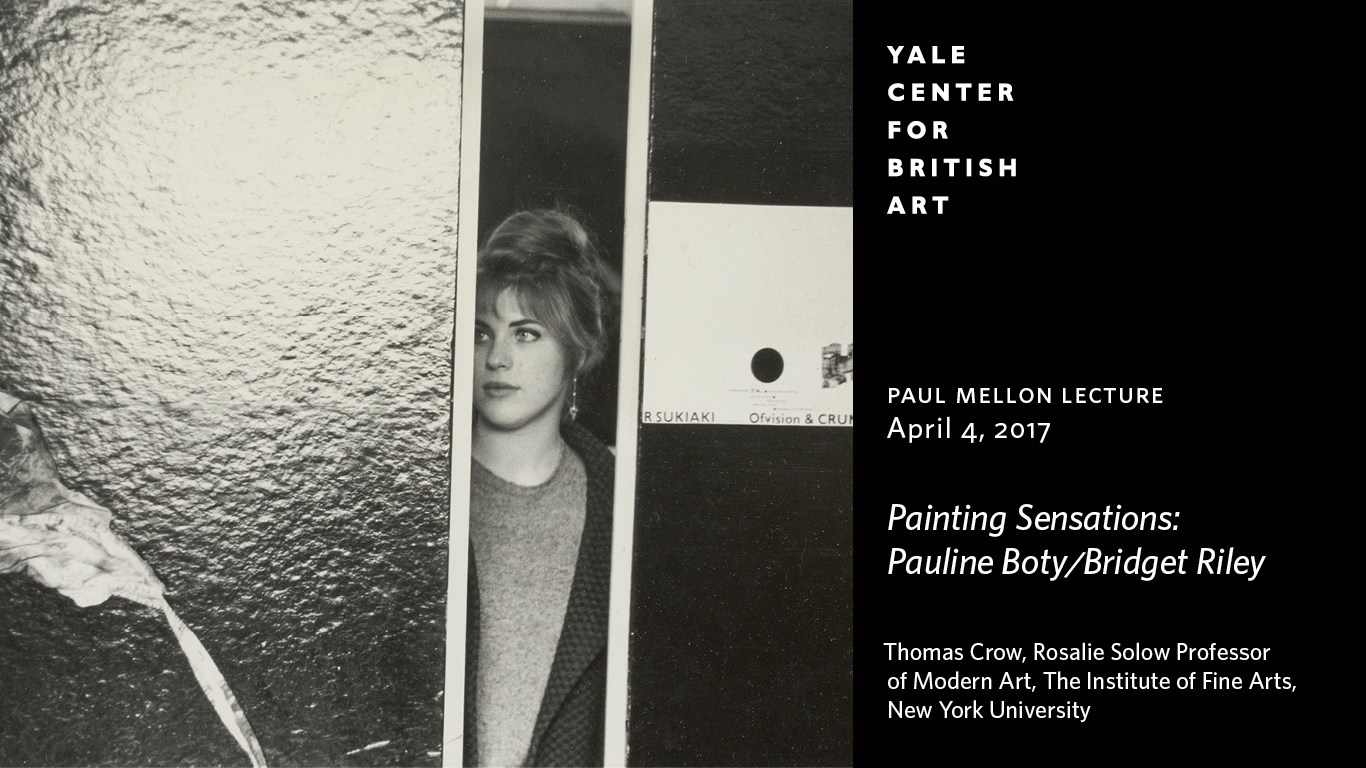

Painting Sensations: Pauline Boty/Bridget Riley

Paul Mellon Lecture

April 4, 2017

Thomas Crow, Rosalie Solow Professor of Modern Art, The Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

By the mid-1960s, the mass media caught up with the modernist style pioneers. Mod-inspired cinema, broadcasting, and glossy print gave unprecedented visibility to women artists—Pauline Boty and Bridget Riley in particular, but at serious cost to the legacies of both.

The Paul Mellon Lectures are given biennially by an invited specialist in British art, first at the National Gallery, London, with the support of the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, and again at the Yale Center for British Art. This year’s five lectures, delivered by Thomas Crow and entitled Searching for the Young Soul Rebels: Style, Music, and Art in London, 1956–1969, are the twelfth in the series. They were given at the National Gallery in London earlier this winter and are being held in the Center’s Lecture Hall on the following dates: March 28, 29; April 4, 5, 12.

These lectures look at the late 1950s emergence of the modernist style among youthful connoisseurs of advanced American jazz and how it fostered a favorable climate for signature British artists of the 1960s—Robyn Denny, David Hockney, Pauline Boty, Bridget Riley, Bruce McLean, and Terry Atkinson, among them.

Thomas Crow’s teaching and research at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, where he is Rosalie Solow Professor, reach from the later seventeenth century in Europe to the contemporary in both Europe and America. His first book, Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Paris, was quickly recognized as providing a fresh model for understanding the art and larger culture of its period. At the same moment, his much-reprinted essay, “Modernism and Mass Culture in the Visual Arts,” identified interdependency rather than antagonism between modern fine art and popular visual expression. All of these concerns—the broad social history of artistic form and reassessing cultural hierarchies alongside the individual formations of artists—came together in his recent, warmly received Long March of Pop: Art, Music, and Design, 1930–1995.