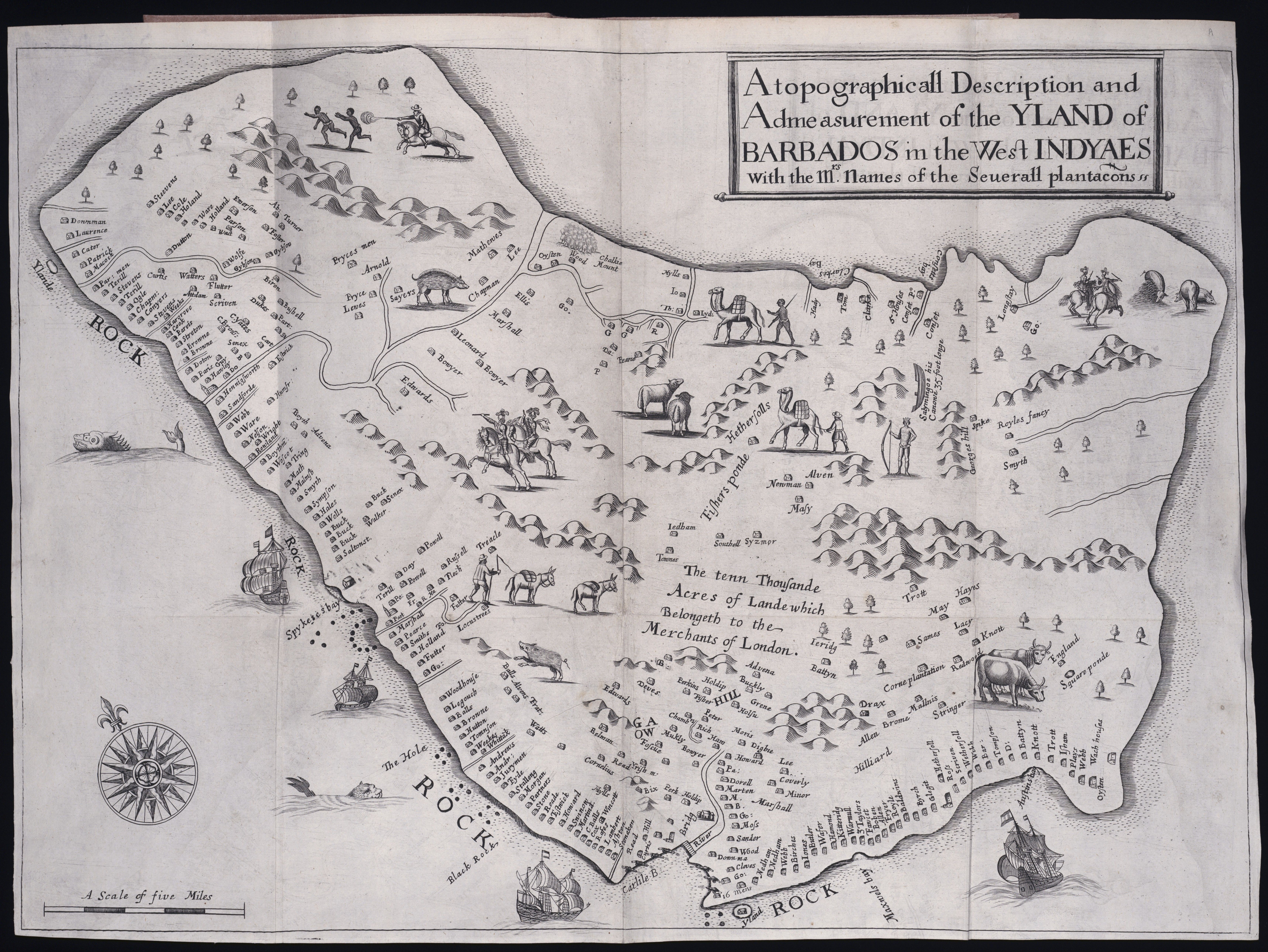

The Island of Barbados, ca. 1694, is the earliest known painted depiction of the easternmost Caribbean island, which became a British colony in 1627. Barbados’s location means it is the first possible landfall in the Caribbean region for ships traveling westbound from Europe and Africa, making it an important transportation node in the colonial era. The British transformed the island into a plantation economy centered on the cultivation of sugarcane and its byproducts, ultimately making it Britain’s most profitable colonial possession in the second half of the seventeenth century. The generation of those riches came at a tremendous human cost, as it depended on the forced labor of enslaved African and Indigenous peoples.

Beginning in 2023, this early depiction of British colonialism in the Americas became the subject of focused study at the Yale Center for British Art, which included in-depth archival research, technical analysis of the painting’s materials and techniques, and a full restoration by the conservation team. The following micrograph enlargements of The Island of Barbados reveal details of various figures populating the painting, many of which have become far more visible as a result of the painting’s conservation treatment. The painting offers significant insight into seventeenth-century Barbados, the nature of plantation enslavement in the British colonies, and the contemporaneous British understanding of that brutal system.

The YCBA is working in partnership with the National Trust in the UK and the Barbados Museum and Historical Society (BMHS), two other institutions that each hold a large-scale painting of the island made after the YCBA’s work is thought to have been completed. There are many unanswered questions about these three paintings, including who commissioned them (and when), who painted them, and how they were understood in their own time. The collaboration between these organizations across the Atlantic has encouraged an exchange of knowledge and technical analysis. In January 2025, staff from the YCBA and the Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage, Yale University, traveled to Barbados to support the BMHS’s technical study of its island painting as well as other works in its collection. Experts on Barbadian history, maritime history, and seventeenth-century art in Europe and the Caribbean have also come together through this alliance to generate further insight into these complex paintings.

The Island of Barbados

The Island of Barbados is a large painting, more than 3½ feet tall and 7½ feet wide. It depicts Barbados from an imagined vantage point high above the sea, looking approximately northeast toward the island’s primary settlement and present-day capital, Bridgetown.

It is unlikely that the painter ever visited Barbados, as the painting does not depict the landscape or architecture accurately. The artist’s depiction of the island appears to be derived in part from Richard Ligon’s 1657 book A true & exact history of the island of Barbados and its accompanying map and illustrations. Ligon had lived in Barbados from 1647 to 1650 while working as a plantation manager, and his book included descriptions and illustrations of features that can also be found in the painting, from the tall palm trees to the enslaved laborers in the sugarcane fields.

The People

The Island of Barbados contains many small details that are crucial to its full understanding but that can be difficult to see with the unaided eye, even when studying the work at close range.

The artist included a number of minuscule figures and features, some painted with only a few brushstrokes. These spare renditions show the island’s settlements and people, as well as the sugar industry that dominated its land, economy, and social structures. The painting as a whole acts as a historical record of the violent system of enslavement that underlay the prosperity of Barbados and British imperial power in the Americas.

While some of these figures were visible in the painting before cleaning, recent restoration work by Kendall Francis, a conservator at the YCBA, has revealed many more. Francis discovered that many of the representations of enslaved Africans had been almost entirely effaced because of previous overcleaning, as some brown pigments are particularly sensitive to the strong solvents and abrasive techniques that were used by conservators in the past. Much like the paint in which they are rendered, these figures’ stories had faded over time. Francis’s treatment of the painting helped restore some of the details that revivify these human histories and the concurrent horrors of plantation slavery.

Black Figures in the Fields

The painting depicts sugarcane fields throughout the island’s interior. In these details, enlarged by a micrograph, Black figures labor in the field while overseen by a white man. Field laborers in Barbados suffered from the tropical heat and extreme physical exertion, often while deprived of adequate nutrition, and were subject to the violence of the white planters. Here, many of the enslaved laborers wear only breeches (short trousers), in contrast to the white man in fashionable European dress, with a long coat, stockings, cravat, walking stick, and hat.

Thatched Hut for Grinding Sugar

This detail depicts an open-air thatched hut with milling machinery being used to grind the sugarcane after harvest. Enslaved Black laborers provide the power to turn the mill, again while supervised by a white man in European dress. To the left, a man sits and smokes. As with many Black figures in the painting, the man’s head was lost to previous overcleaning and has been reinstated during the recent conservation treatment.

This is a misleading image of the sugar-production process, indicating that the artist may have been unfamiliar with the details of the industry. In the seventeenth century, sugar mills were much larger than shown here, and were usually located indoors and powered by animals such as donkeys or oxen. The painting also does not include a detailed representation of a boiling house, the hellishly hot and chaotic building where the sugarcane juice was reduced to molasses. Planters considered their enslaved workers’ lives to be expendable, and the mill machinery and molten sugar were both extremely dangerous, especially because sugar mills and boiling houses operated around the clock during the harvest seasons, driving the workers to exhaustion. Appalling injuries and deaths resulted from the planters’ avarice and disregard for human life.

Indigenous People on the Island

The figures in these details may be intended to represent peoples indigenous to North and South America who were brought to Barbados and enslaved in the seventeenth century. The artist chose a lighter brown pigment for their skin tones, distinguishing them from the Black laborers; they do not wear European clothing, and some appear to be working in the fields. Before European colonization, Barbados was frequented by Kalinago peoples. However, when the British arrived, the island was apparently uninhabited, either because of seasonal migration or a decision to fully abandon the island after previous incursions by the Spanish.

In 1627, the first year of British settlement on Barbados, the British transported a group of Arawaks from the northern coast of South America to teach the settlers how to grow tropical food staples such as cassava and sweet potato and the cash crops tobacco and sugar. According to period accounts by the British colonists, the Arawaks came to the island willingly. However, the British broke their promises of freedom and enslaved them until the 1650s.

In the 1670s, the New England colonies went to war with neighboring Indigenous groups who had been resisting European control. In retaliation, the British trafficked many Algonquian-speaking people from Connecticut and other colonies to Barbados and elsewhere in the Caribbean. This punishment was meant to break up cultural groups and reduce the Indigenous population in the region, paving the way for further white settlement in New England.

Women on the Island

In the early days of Barbados’s colonization, men far outnumbered women, especially among the white settlers. The artist included three women, all white, in this composition: two on board a ship, and another standing with a man at the entrance to one of the settlements. White women were often beneficiaries of the social and racial hierarchies on the island; women from the planter class in particular profited from the wealth generated by enslaved labor and sometimes owned and managed plantations directly.

Close analysis of the painting reveals traces suggesting a Black woman moving through the landscape with a child on her back. As Richard Ligon described in A True and Exact History of Barbados, a fortnight after giving birth, mothers were forced back into the fields with their infants strapped to their backs. They endured hours of painful, stooped labor made worse by the effects of childbirth and the burden of childcare.

White Laborers

These three dockworkers are the only white laborers depicted in the painting. They appear prominently in the center foreground of the painting, in front of a fort, where they are using a smaller boat to transport goods between the shore and an anchored ship.

In the early decades of the colonization of Barbados, many white men arrived as indentured servants. While some willingly traveled to Barbados to avoid debtors’ prison or poverty, others were forcibly transported—a canny way for the British government to furnish much-needed colonial labor while removing political dissidents from Ireland and Scotland.

Indentured servants signed contracts agreeing to work for a set number of years before gaining freedom. Many found it difficult to purchase land or acquire wealth after their service. Some moved to Bridgetown to work, while others left the island. The number of indentured servants declined rapidly by the 1660s, as white settlers sought success elsewhere and the landowners of Barbados turned primarily to the slave trade for plantation labor.

The dockworkers depicted in The Island of Barbados may have been indentured servants, former indentured servants, or perhaps their descendants, who formed a lower class of white laborers in the Barbadian hierarchy.

Ships in the Water

The ships depicted in the waters around the island were a crucial part of the global trade system that made Barbados such a profitable colonial holding. The majority of these vessels fly flags with the red-and-white Saint George’s Cross, typically an indication that they are merchant, rather than naval, ships. However, the ship in this detail is likely a Royal Navy gunboat, as indicated by the royal coat of arms on the stern. The Royal Navy’s protection was key to the safety of merchant shipping operations. Indeed, the wealth and power of the British Empire were tied directly to its mercantile success, including its transactions in enslaved African lives. It is estimated that British traders trafficked at least three million Africans from West Africa to the Americas between 1640 and 1807, when the trade was officially abolished.

This web story, written by Sarah Mead Leonard during her time as a Postdoctoral Associate in the YCBA’s Research Department, is part of a larger project exploring The Island of Barbados and two other early paintings of Barbados in the collections of Dyrham Park (National Trust, UK) and the Barbados Museum and Historical Society. The author would like to acknowledge the input of her project collaborators, including Kendall Francis; Edward Town; staff of the National Trust, the BMHS, and the Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage; and many outside scholars.

Learn more about the Views of Barbados project here.

Published May 2025.