Sir Joshua Reynolds’s portrait of Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and Marcus Richard Fitzroy Thomas

In May 2022, the Yale Center for British Art retitled Joshua Reynolds’s portrait of Charles Stanhope to include the identity of the child in the picture, now known to be Marcus Richard Fitzroy Thomas (ca. 1768–1816). This marks the first time in the painting’s 240-year exhibition history that both figures are named.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and Marcus Richard Fitzroy Thomas, 1782

When it was first shown at the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition in 1783, the painting was listed in the official catalogue as Portrait of a Nobleman.(1) Such nonspecific titles were typical of portraits displayed at the RA until the end of the eighteenth century.(2) Indeed, none of the portraits Reynolds exhibited in 1783 were listed under their sitters’ names, with the characteristic result that three of his works were shown as Portrait of a Gentleman.(3) The intent was not to cloak identities in secrecy:(4) exhibition reviews freely disclosed sitters’ details.(5) Rather than anonymizing their subjects, these generic titles, based on age and gender, and most of all on class, placed the paintings, and by extension their subjects, within what scholar Ruth Yeazell calls a “language of classification,” encouraging comparison between portraits of sitters of comparable social standing.(6)

Yet some sitters did remain anonymous. Late-eighteenth-century viewers of Portrait of a Nobleman were primed to view it as having only a single subject, despite the presence of two people in the composition. A sketch of the painting made at the 1783 Royal Academy exhibition exemplifies this erasure: the artist Edward Francis Burney abbreviates the composition left and right and omits the figure of the attendant entirely. Likewise, a review of the painting in the Morning Herald that year made no mention of a second figure, referring only to the “objects in the background,” which Reynolds had painted with good “effect.”(7)

In 2014, when the portrait was included in the exhibition Figures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain at the Yale Center for British Art, it was displayed under the title Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and a Servant.(8) The generic term “servant,” unlike “nobleman” or “gentleman” in 1783, was not intended as a means of classification. Rather, it was used out of necessity because Thomas’s name was not yet known. In the context of the 2014 exhibition, and subsequently for modern-day audiences, it has been not Stanhope but the unknown figure who has garnered the most interest and, as art historian Erica Moiah James has noted, seemed “most human.”(9) When the artist Titus Kaphar cited a figure from the Reynolds portrait in his recent painting Seeing Through Time 5 (2019), it was Stanhope and not the person we now know to be Marcus Thomas whom he ignored.(10)

Identifying Marcus Richard Fitzroy Thomas

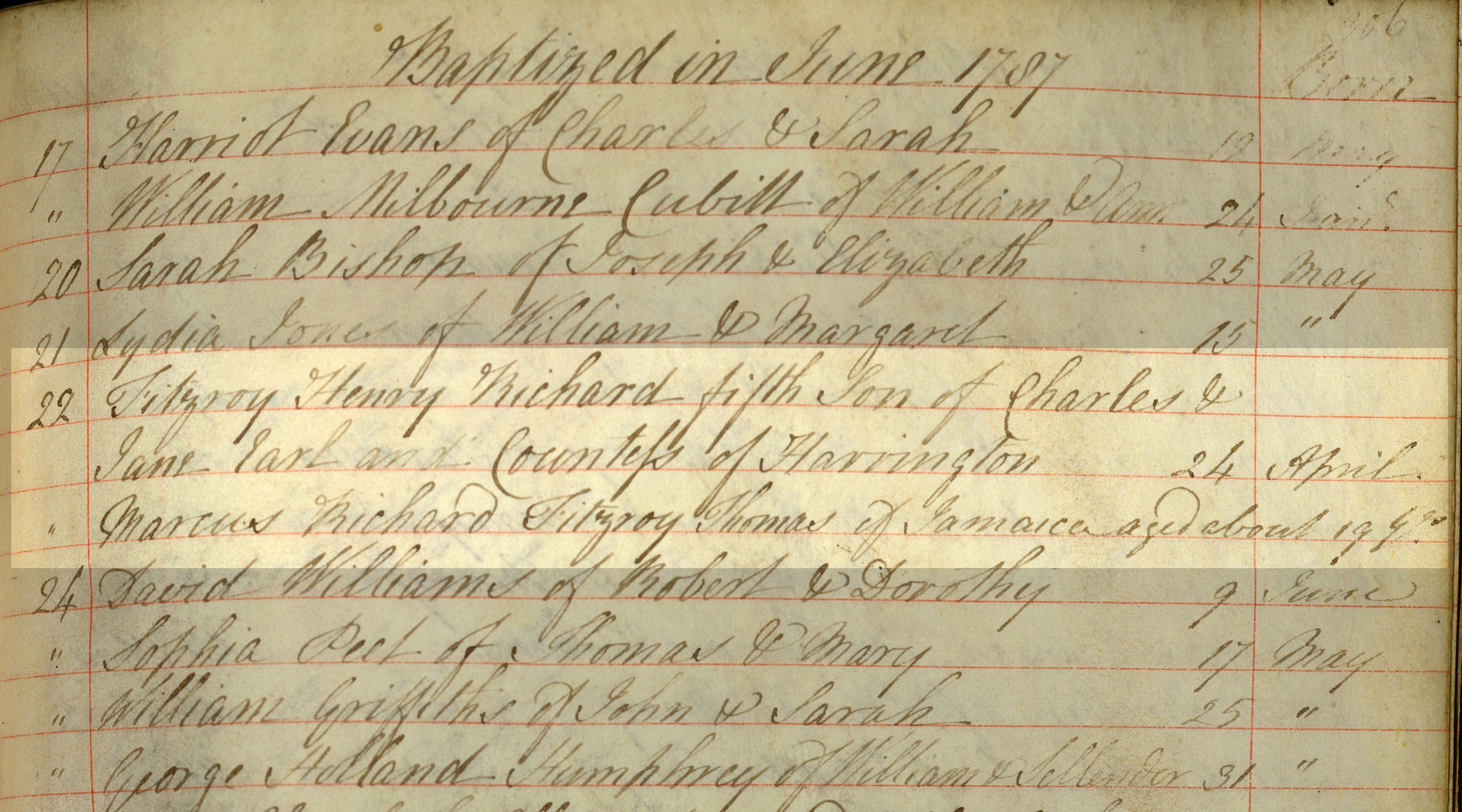

In fall 2021, Alice Millard, a researcher at the West Sussex (UK) Record Office, contacted the YCBA with a lead relating to the identity of the unnamed child in Reynolds’s portrait.(11) While surveying the eighteenth-century parish register of New Shoreham, West Sussex, she encountered the name of Marcus Thomas, described as a “negro man.” He was listed alongside his wife, Elizabeth, as parent to a newborn boy, John Henry Thomas, who was baptized on April 2, 1794. Further inquiry led Millard to Marcus Thomas’s own baptism record, found in the parish register of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, London. Dated June 22, 1787, it reads: “Marcus Richard Fitzroy Thomas of Jamaica aged about 19 y[ea]rs.” The fact that he was from Jamaica, then a British slave colony; the uncertainty about his age; and the absence of listed parents suggest that Thomas had been enslaved in Jamaica prior to residing in London.

Significantly, the entry directly above that of Marcus Thomas lists the baptism of a Fitzroy Henry Richard, described as the “fifth son of Charles & Jane [Stanhope] Earl and Countess of Harrington, [born on] 24 April [1787].”(12) The names shared by Marcus Richard Fitzroy Thomas and the earl’s infant son, and the fact that they were the only two people baptized on June 22, indicate that Thomas was closely connected to the Stanhope family. Upon noting this relationship, Millard found Joshua Reynolds’s portrait of Charles Stanhope in the YCBA’s online collection and asked the question: Could the child in the portrait be Marcus Thomas? It seemed possible, given that he appears to be thirteen or fourteen years old in the painting, which accords with Thomas’s approximate age at the time Reynolds painted it in 1782, but it was impossible to say for certain.

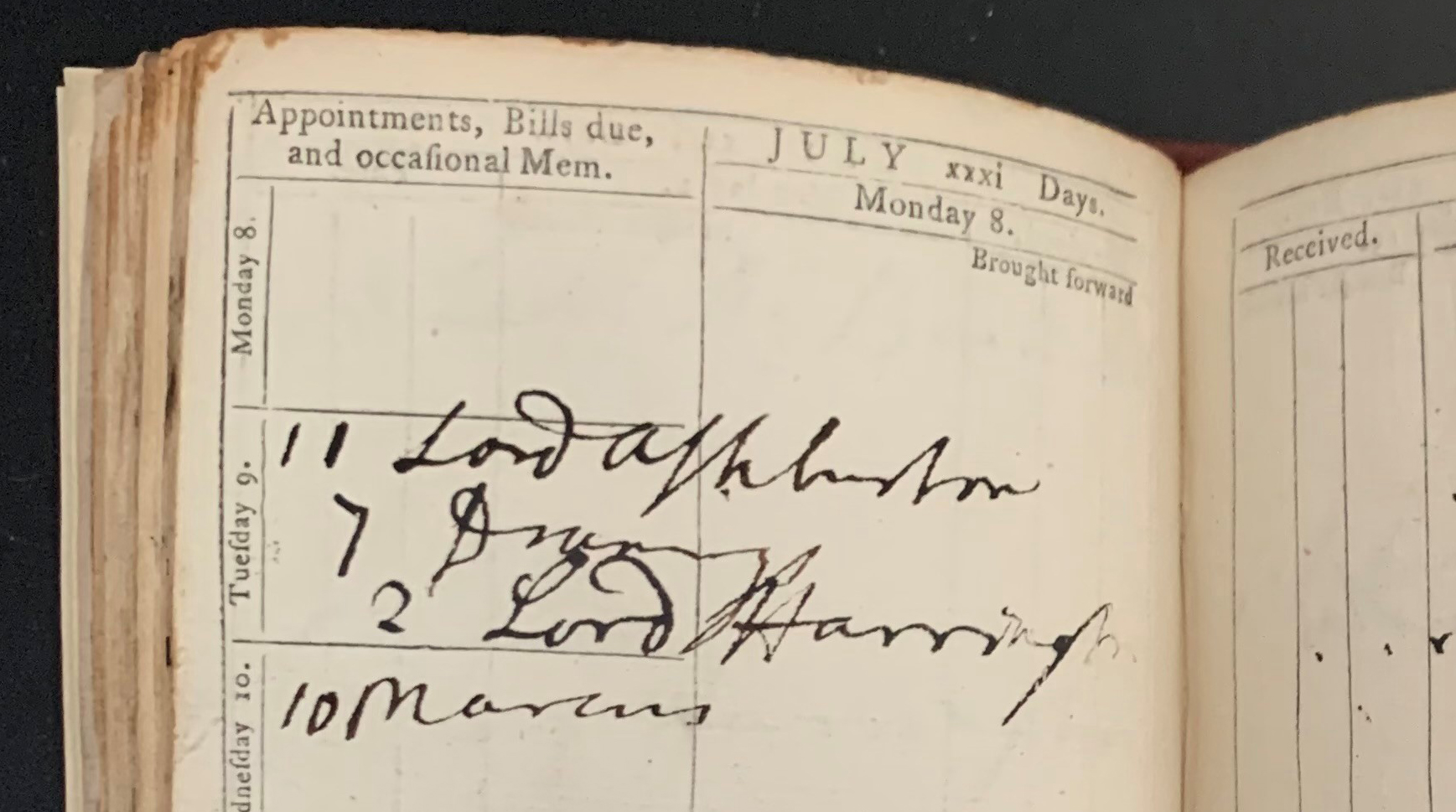

It is within Reynolds’s sitter books—ledgers in which he recorded his appointments at his Leicester Square painting studio with his patrons, sitters, and models—that a definitive answer is found.(13) Although the entries are succinct—consisting of the date, time, and sitter’s name, or in some cases only a description of the sitter—the notebooks have long been an invaluable resource for scholars of Reynolds’s artistic process. Turning to Reynolds’s sitter book for 1782, we find that the artist had twelve meetings with Charles Stanhope that summer: four per month in June, July, and August. The most important, in terms of linking Marcus Thomas to the painting, is the meeting on July 9 at 2 pm. There is nothing unusual about this individual entry, but as with the St. Martin-in-the-Fields baptism register, looking beyond the individual record reveals another piece of revelatory data on the page. Immediately below “Lord Harrington” is an entry marking Reynolds’s next appointment, which took place at 10 am the next day. The artist listed this sitter simply by his first name: Marcus.

It is not surprising that this entry and its potential connection to the portrait of Charles Stanhope have previously been overlooked, despite the scholarly attention that Reynolds’s sitter books have received. Without the biographical information provided by the St. Martin-in-the-Fields baptism record, there would be no way to recognize a connection between “Marcus” and “Lord Harrington.” On its own, the recorded name “Marcus” does not suggest itself as a possible identity for the boy in the painting. When logging sittings with other Black models, such as the unidentified woman who appears in his portrait of Lady Elizabeth Keppel (1762), Reynolds often wrote only the word “negro,” with no other identifying information.(14) The use of Thomas’s first name is an unexpected departure from these more typical “terse archival traces;”(15) it is an exceptionally rare instance of an eighteenth-century London-based artist recording the identity of a Black sitter.

While Marcus Thomas and Charles Stanhope are thus connected on the page in the archival record and on canvas in Reynolds’s portrait, the question remains: What was their real-life relationship? Even without knowing Thomas’s name, art historians have suggested plausible answers. When the painting was featured in the exhibition Figures of Empire, the curators Esther Chadwick, Meredith Gamer, and Cyra Levenson posited that the boy may have been connected to Stanhope’s Jamaican regiment or his London household, both of which are likely.(16)

After serving in the American Revolutionary War, including the notorious defeat at Saratoga under General John Burgoyne in 1777, Charles Stanhope succeeded his father to become the third Earl of Harrington in 1779. Soon after, he married Jane Fleming. She was a well-known society heiress and stepdaughter to Edwin Lascelles, first Baron Harewood, a prominent owner of plantations in Barbados, Jamaica, and Tobago.(17) The newly married Stanhopes traveled to Jamaica in 1780 with the 85th Regiment of Foot; Charles, who was colonel, had raised the regiment at his and his wife’s own expense with the charge to protect the British slave colony from a potential French invasion, which never materialized. Charles’s younger brother, Henry Fitzroy Stanhope, also commanded troops in the Caribbean and did encounter the French; for his role in the surrender of Tobago to French troops in 1781, he was court-martialed in London and ultimately acquitted.(18) Illness precipitated Charles and Jane Stanhope’s return to London from Jamaica in 1782; they were soon followed by the entire 85th Regiment, which disbanded at Dover Castle in 1783.(19)

Marcus Thomas would have been around twelve when Stanhope’s regiment arrived in Jamaica in 1780, but his youth would not have precluded his becoming attached to the regiment. During this period, British colonels in the Caribbean were known to “gift” their regiments with enslaved boys and young men, many of whom served as drummers, a practice that dates back to the seventeenth century.(20) If this, or something similar, was Thomas’s experience, it is plausible, given Jane Stanhope’s family connection to slavery, that he encountered Charles on one of the Lascelles’ Jamaican plantations prior to joining the regiment.(21) The muster roll for the 85th’s final months in Dover suggests that it did in, fact, return to Britain with drummers of African descent among its ranks, one of whom is recorded under the name “Thos. Africanus.”(22) The name Thomas is noteworthy, and this may indeed refer to Marcus Thomas. However, the use of a last name in conjunction with the patrial name “Africanus” (presumably a mordant allusion to the ancient Roman general Scipio Africanus) would be unusual. “Africanus” was likely conferred in the absence or in lieu of a family name, suggesting that in this case “Thos.” is the first name of someone other than Marcus Thomas.(23) Even if Marcus Thomas is not documented in the regimental archive, however, he may have served in another capacity as an attendant, groom, or laborer, his name, if recorded, part of a document now lost.

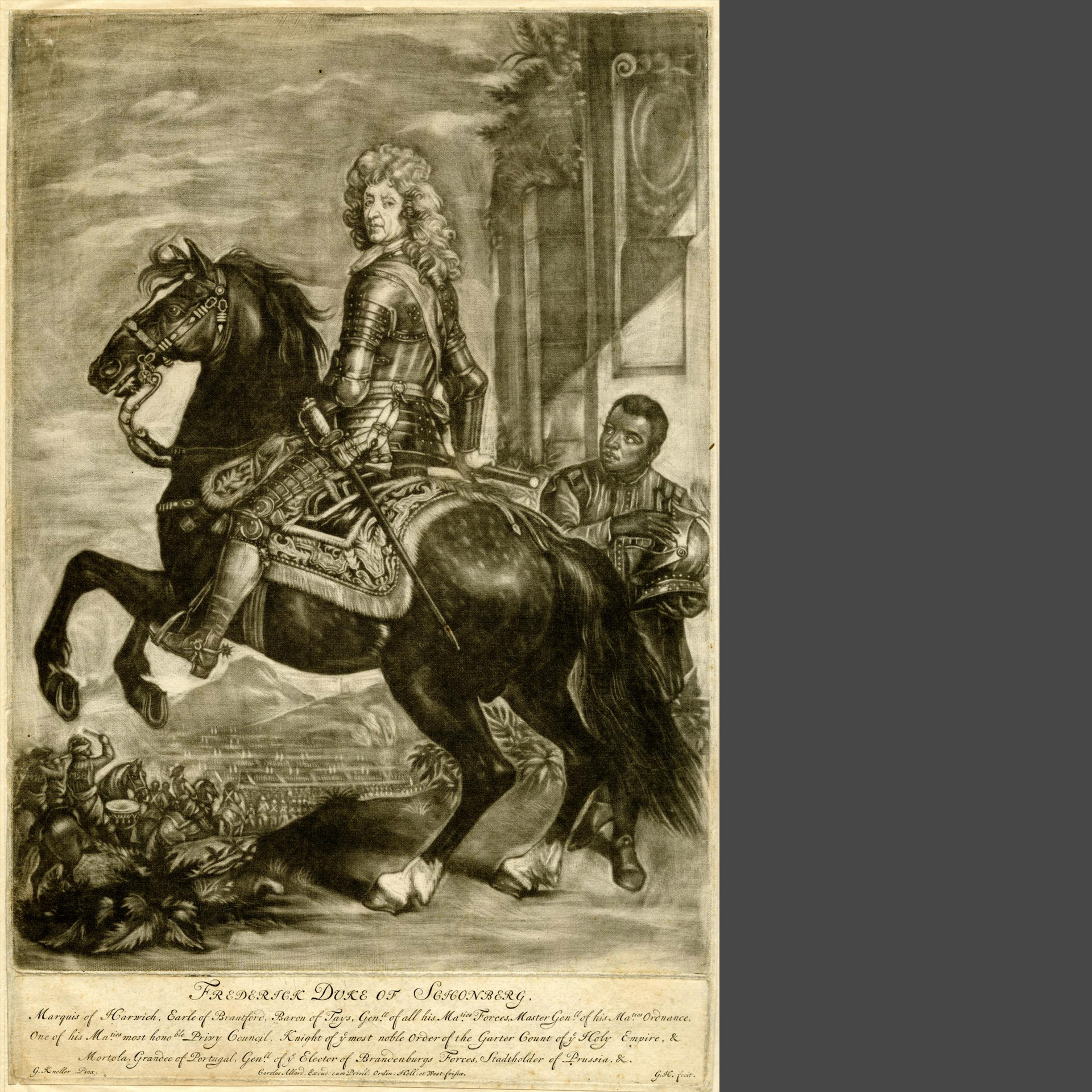

The military nature of Reynolds’s portrait implies that the relationship between Stanhope and Thomas was regimental, even as the composition draws from stock conventions of European portraiture. When it was displayed in Figures of Empire, the curators noted the painting’s clear debt to the French artist Hyacinthe Rigaud’s portrait of the King of Poland and an unnamed Black attendant (A).(24) Both Rigaud’s and Reynolds’s compositions contrast the central figure’s static stance, based on the pose of the Apollo Belvedere, with the action of the attendant, who leans in from the side holding the central figure’s helmet. Another influence appears to have been Godfrey Kneller’s seventeenth-century equestrian portrait of Frederick, Duke of Schonberg, known via John Smith’s mezzotint copy, in which an unidentified attendant similarly holds the central figure’s helmet at the right of the composition (B).(25) Reynolds’s painting of Stanhope and Thomas omits the horse and architectural details from Kneller’s composition but retains the scene of combat, painted in hazy sfumato on the lower left, to suggest Stanhope’s military command.(26) This battlefield vignette was deemed an important piece of visual propaganda, as is evinced by the way Stanhope and Thomas have been awkwardly pushed to the right side of the composition to accommodate it. Another element retained from Rigaud’s and Kneller’s portraits is Stanhope’s armor, an unusual anachronism given that Reynolds usually painted his military sitters in contemporary uniform (see, for instance, the artist’s portrait, ca. 1766, of Stanhope’s former commander General John Burgoyne).(27) Ostensibly removing the painting from the particulars of the present, the armor perhaps manifests the temporal abstraction Reynolds recommended for “grand-manner” portraiture in his Discourses on Art.(28) Stanhope’s archaic attire also gestures toward the historical self-presentation of his family, who had been ennobled for their military achievements; his grandfather, the first Earl of Harrington, is depicted in a similar suit of armor in a half-length portrait attributed to Kneller (C).(29)

As evinced by Reynolds’s source material, Stanhope’s decision to be pictured alongside a Black attendant in a manner explicitly drawn from historical precedents in European portraiture places him among a large, heterogenous group of art patrons. Despite their varied status, aristocrats, merchants, “the commanders of slave ships, returned plantation owners, colonial officials and soldiers, [and] kings and queens” were united, as historian David Olusoga has pointed out, in their desire to telegraph proximity to empire and the institution of slavery through the visual objectification—signifying the physical subjugation—of Black children, women, and men.(30) While the picture belongs within this broader context, it is also important to acknowledge it as a product, and a record, of the specific intersection of the sitters’ lives, based on the particulars of their lived experience.

The appearance of “Marcus” in Reynolds’s sitter book on July 10, 1782, is the earliest record we now have of Thomas’s presence in London. The Stanhopes probably brought Thomas to the city upon their return from Jamaica earlier in the year. By the time he sat for Reynolds, he had likely become a servant in the family’s London household at Harrington House, on Stable Yard Road in St. James. The house was demolished in 1830, however, so any archival trace of his presence there, if it once existed, may now be lost.(31) Reynolds’s portrait, although military in nature and based on pre-existing iconography, may hint at the change in Thomas’s role within the family. While the jacket Thomas wears in the painting resembles a regimental uniform, although not in keeping with the red jackets worn by the 85th Regiment, it also suggests the liveries worn by household servants in eighteenth-century Britain.(32) Further research might determine if the jacket corresponds to the livery then worn at Harrington House or at the family’s country seat, Elvaston Castle in Derbyshire. (Charles Stanhope’s son, the fourth Earl of Harrington, later famously dressed his household staff in brown livery.(33)) The way Thomas holds Stanhope’s helmet might also be read with this double meaning; that is, as connoting both military and domestic service.

It is, however, impossible to know the specific nature of the shift in Thomas’s role and to establish the character of his life in this period. While slavery was outlawed in Britain after the Somerset ruling of 1772, the status of many Black servants in the British Isles remained ambiguous until the end of the century. As Olusoga has described, determining how the “borders” between enslavement and servitude were “policed and managed” in eighteenth-century British homes is difficult: “the likelihood is that it varied enormously from family to family and from case to case.”(34)

Visual and material clues found in the painting itself, as well as the circumstances surrounding its production, provide conflicting evidence regarding the nature of Thomas’s relationship with Stanhope, and Reynolds’s engagement with him as a sitter. The significance of his being named in the sitter book cannot be overlooked, but it is telling that, in contrast to Stanhope’s twelve appearances, “Marcus” is recorded only once. Some of Stanhope and Reynolds’s meetings may have been consultations rather than dedicated sittings, during which the artist and patron may have discussed the composition and Thomas’s inclusion in it, but if we are to assume the accuracy of the sitter book, the artist spent little time with Thomas himself. This disparity parallels that between the eight sittings Reynolds had with Lady Elizabeth Keppel when painting her portrait in 1761–62 and the two sittings he had with the unnamed attendant who appears next to her.(35)

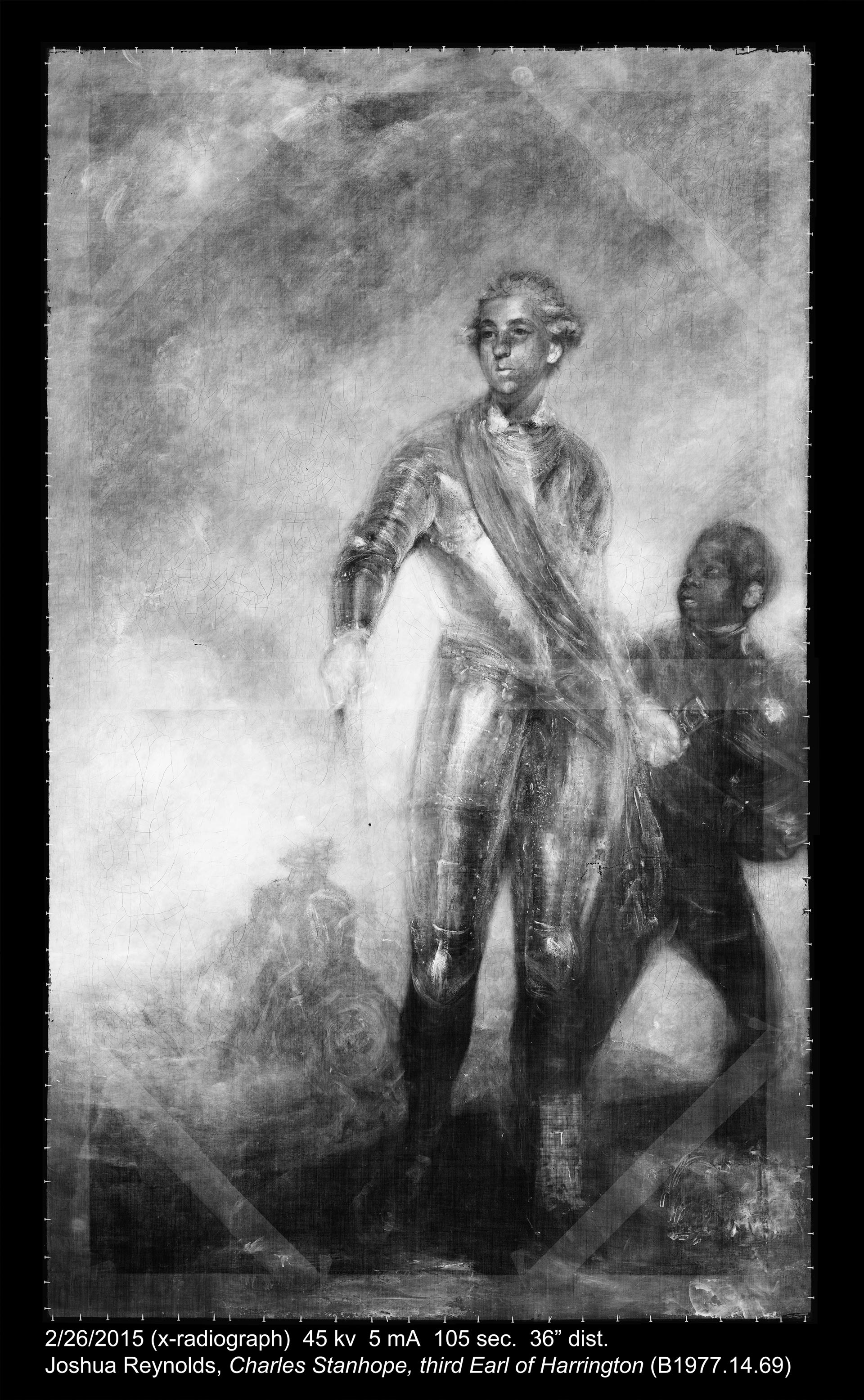

Despite this discrepancy, there is no discernable difference in the way Reynolds painted the faces of Thomas and Stanhope. X-ray imaging reveals a similar level of work, with equal amounts of underpainting, layering, and glazing. This is evinced by the comparable level of craquelure, or cracks and paint wrinkles, surrounding both faces (D and E). X-ray fluorescence imaging, which maps the type and distribution of specific paint pigments, confirms the parity of Reynolds’s treatment: while British artists in the eighteenth century often used different pigment types to paint darker and lighter complexions, Reynolds has used a similar palette, applied in different ratios, to depict Stanhope’s and Thomas’s flesh.(36)

If not in the workmanship, then, perhaps there is a disparity in how closely each painted face resembles its sitter, which might account for the extra time spent with Stanhope.(37) At this time, this is not possible to determine, since there are no other known images of Thomas. Furthermore, although such a discrepancy in likeness is probable, present-day observers of the painting, even without knowing Marcus Thomas’s identity, have noted the child’s palpable sense of personhood and individuality in comparison to similar portraits in which an unidentified Black attendant appears.(38) Where we do find an obvious disparity between the depictions of Stanhope and Thomas is in the relative positioning of their bodies and the space they inhabit in the painting. In preliminary stages of the composition, Reynolds included the full length of Thomas’s legs, as is revealed in the x-ray image of the painting. In the final work, however, the artist covered Thomas’s lower legs and feet with a curious hill that defies perspectival logic but functions to serve the class- and race-based hierarchical logic of the picture and of eighteenth-century British society. While Reynolds may have made this change to the composition to obscure the awkward overlap of the figures’ legs, it also reduces Thomas’s presence, rendering him even smaller than Stanhope and pushing him further back into the painting’s middle ground.

Just as it is challenging to parse the significance of Marcus Thomas’s appearance in Reynolds’s sitter book and in the painting itself, it is also difficult to know the spirit in which Thomas assumed the middle names “Richard Fitzroy,” names which he shared with Stanhope’s son Fitzroy Henry Richard and which he kept throughout his life.(39) His baptism in 1787, five years after the painting’s completion, was likely the occasion when he was given or adopted these names, perhaps marking a change in his relationship to the family, although baptism did not necessarily indicate freedom or departure from service.(40) It appears that Thomas remained in London for at least six more years until his marriage in 1793 to Elizabeth Plaxton, recorded in the parish register for St. Martin-in-the-Fields. (Thomas signed his marriage record with an X, indicating he had not been taught how to read or write during his time in the Harrington household.(41)) It was not until 1794 that he moved away from London with his wife to the borough of New Shoreham, the coastal port town where their son John Henry was baptized.(42)

Research conducted by Alice Millard has uncovered much more about the Thomases, including the record of young John Henry’s burial in 1797, three years after his baptism.(43) Curiously, this sad event took place in Sunderland, a coastal town in the county of Durham, some 320 miles north of Sussex. Yet by 1801 Marcus and Elizabeth had returned south to Sussex, where, in Bexhill, another port town thirty miles east of New Shoreham, they welcomed a daughter, Anna Maria Jane.(44) The Thomases’ movement between various English coastal towns during this period suggests that Marcus may have found work in the shipping industry or returned to the military. By 1803, however, the family was back in London, where Anna Maria Jane passed away in 1805.(45) Another son, Augustus, died as an infant that year.(46) The deaths of all three Thomas children at such a young age is a tragedy that exceeds even what one might expect from the high infant mortality rate in early-nineteenth-century London, where two-fifths of children died before the age of five.(47)

Marcus Thomas died July 16, 1816, thirteen days after he had been admitted to the St. Martin-in-the-Fields workhouse. He was forty-eight years old.(48) The workhouse in this period had yet to attain the punitive reputation it would assume after the Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834: in the early decades of the nineteenth century it functioned as a refuge, providing housing and medical care to the parish’s impoverished and infirm. Given the short period between his admission and final decline, Thomas was likely transported to the workhouse to receive end-of-life care he could not receive elsewhere.(49) The circumstances surrounding the end of Elizabeth Thomas’s life have yet to be uncovered; she may have preceded her husband in death.

Thomas appears in the workhouse and death records as Marquis Richard Henry Fitzroy Frederick Augustus Thomas. This unusually long name incorporates the names Henry, which belonged to his first son, and Augustus, which he had adopted by the time of his marriage and which he shared with his second son. Significantly, both the names Henry and Augustus, as well as the aforementioned Richard and Fitzroy—not to mention Anna Maria, Marcus’s daughter’s name—are all shared with members of the Stanhope family.(50) The character of the sustained connection this suggests is, as with much about Thomas’s life, difficult to determine. More likely founded on his past relationship with the Stanhopes rather than a continued association, the names nonetheless overtly align Thomas’s family with the aristocratic family who brought him to Britain. It is currently unknown whether this association via the adoption and bestowing of aristocratic names constituted an act of resistance, reverence or something more ambivalent. Much more remains to be uncovered about Thomas’s life in London in the early nineteenth century.

Marcus Thomas’s final trace in the archives, his burial record, reveals that he was laid to rest by the parish in which he had been baptized twenty-nine years earlier. He was buried in Camden Town Cemetery, which had been recently created to manage the overflow from St. Martin-in-the-Fields Parish. It is now a park called St. Martin’s Gardens.(51)

Writing in 2015 of the painting then known as Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and a Servant, Erica Moiah James posed the question, “Must a rendered black child be named in order to have recognized personhood?”(52) Though the question makes its point rhetorically, the answer, of course, is no. As twenty-first century viewers, curators, scholars, and artists have acknowledged in their recent interpretations of Reynolds’s portrait, Marcus Thomas has always been present; we just did not know his name. Nonetheless, the recovery of Thomas’s identity and his name’s inclusion in the portrait’s title mark a significant new chapter in the painting’s exhibition history, in which we fully recognize it as a double portrait even if its contemporaneous viewers did not.

Written by Victoria Hepburn, a Graduate Student Research Assistant at the Yale Center for British Art and a PhD candidate in the History of Art at Yale. She thanks Edward Town, Jessica David, and Martina Droth for their invaluable comments and insights.

Published December 2022.