The title for this exhibition references both the use of the collection of the Yale Center for British Art and Lucy Lippard’s influential collection of feminist essays, From the Center (1976). In it, she states that “the self-consciousness of femaleness, has opened the way for a new context within which to think about art by women.” Nearly forty-five years later we are still discovering new frames through which to appreciate the work of women artists. The artists on display span the nineteenth century to the present day and work across a broad spectrum of media, styles, and techniques.

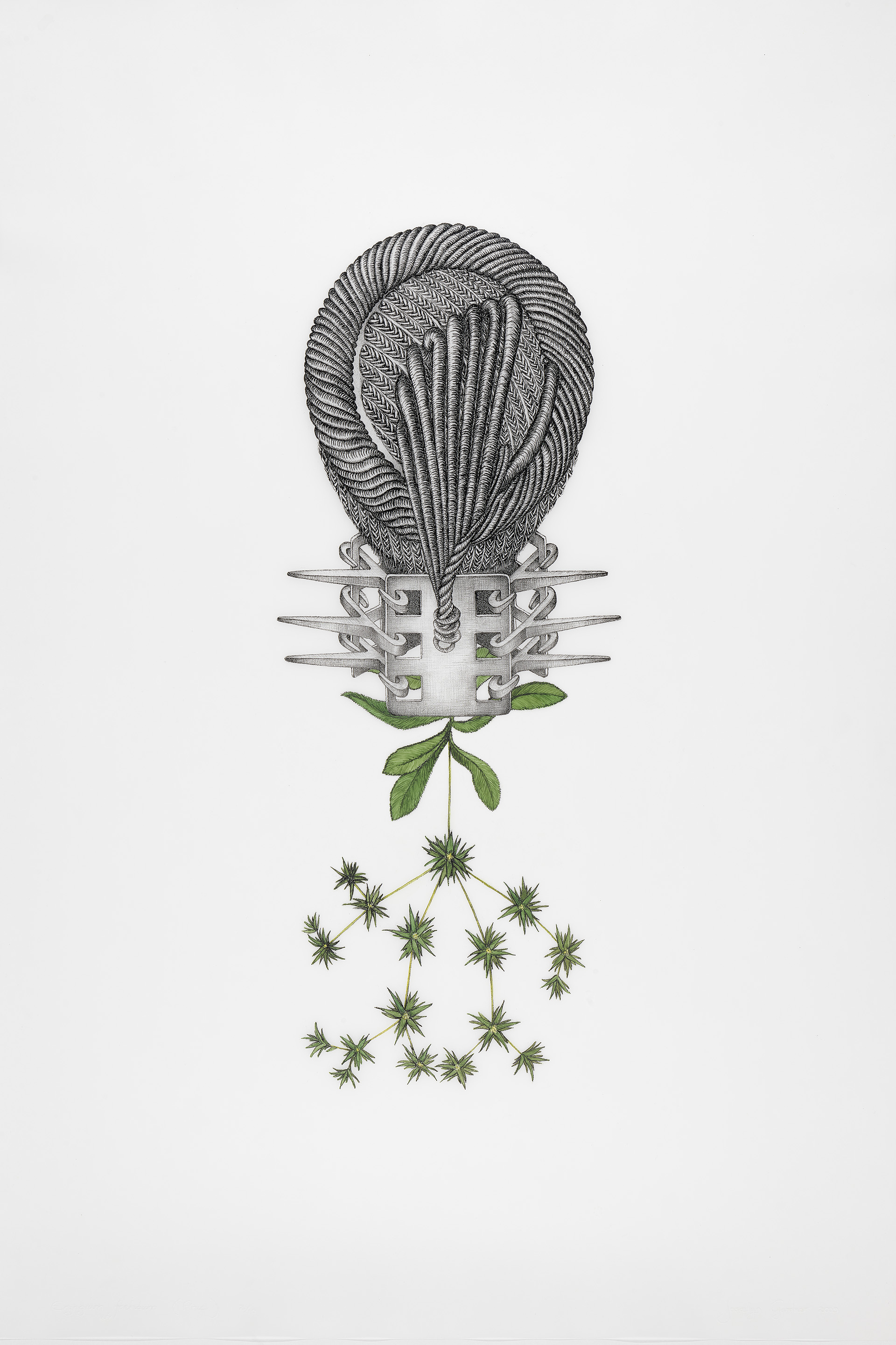

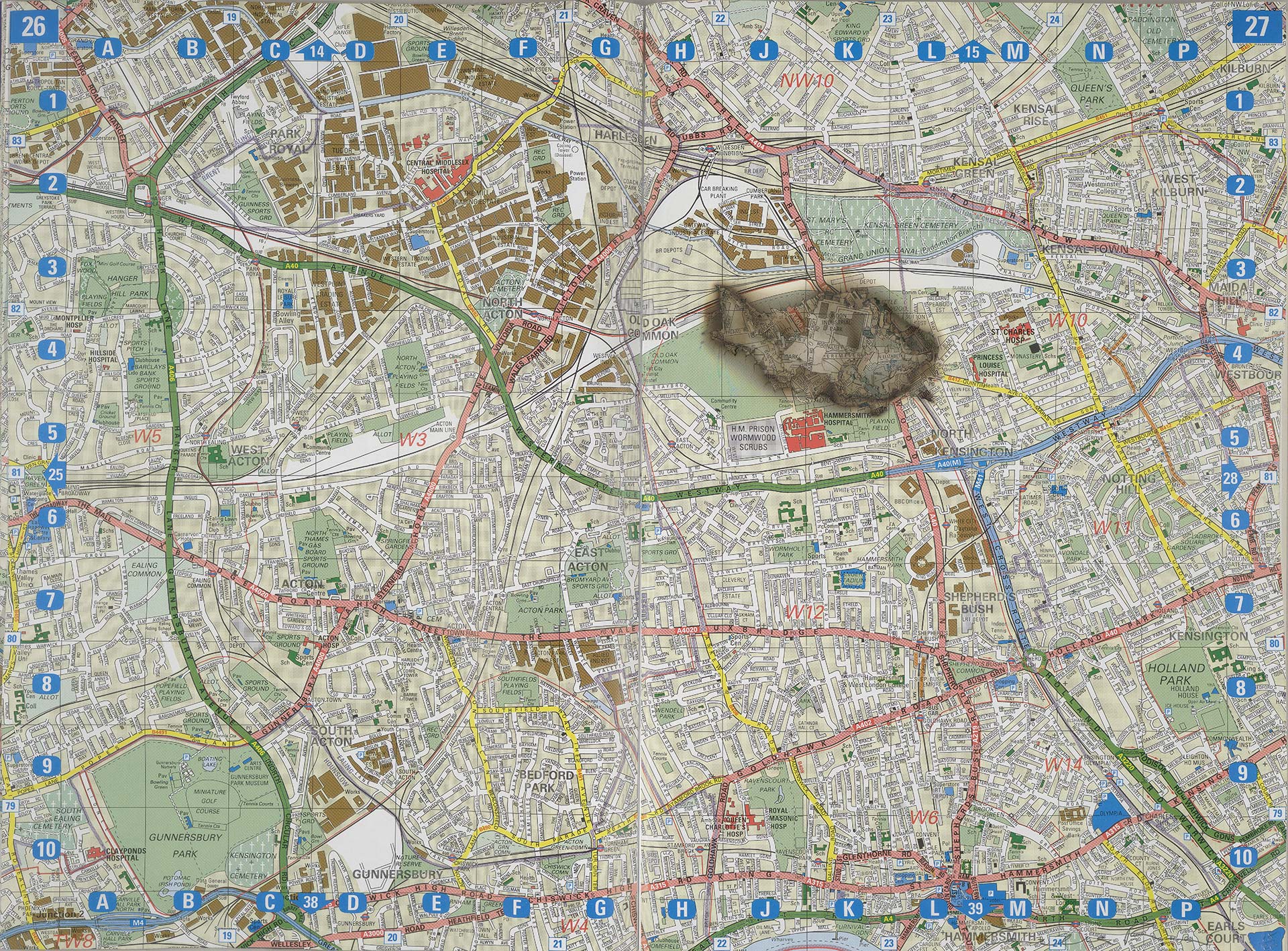

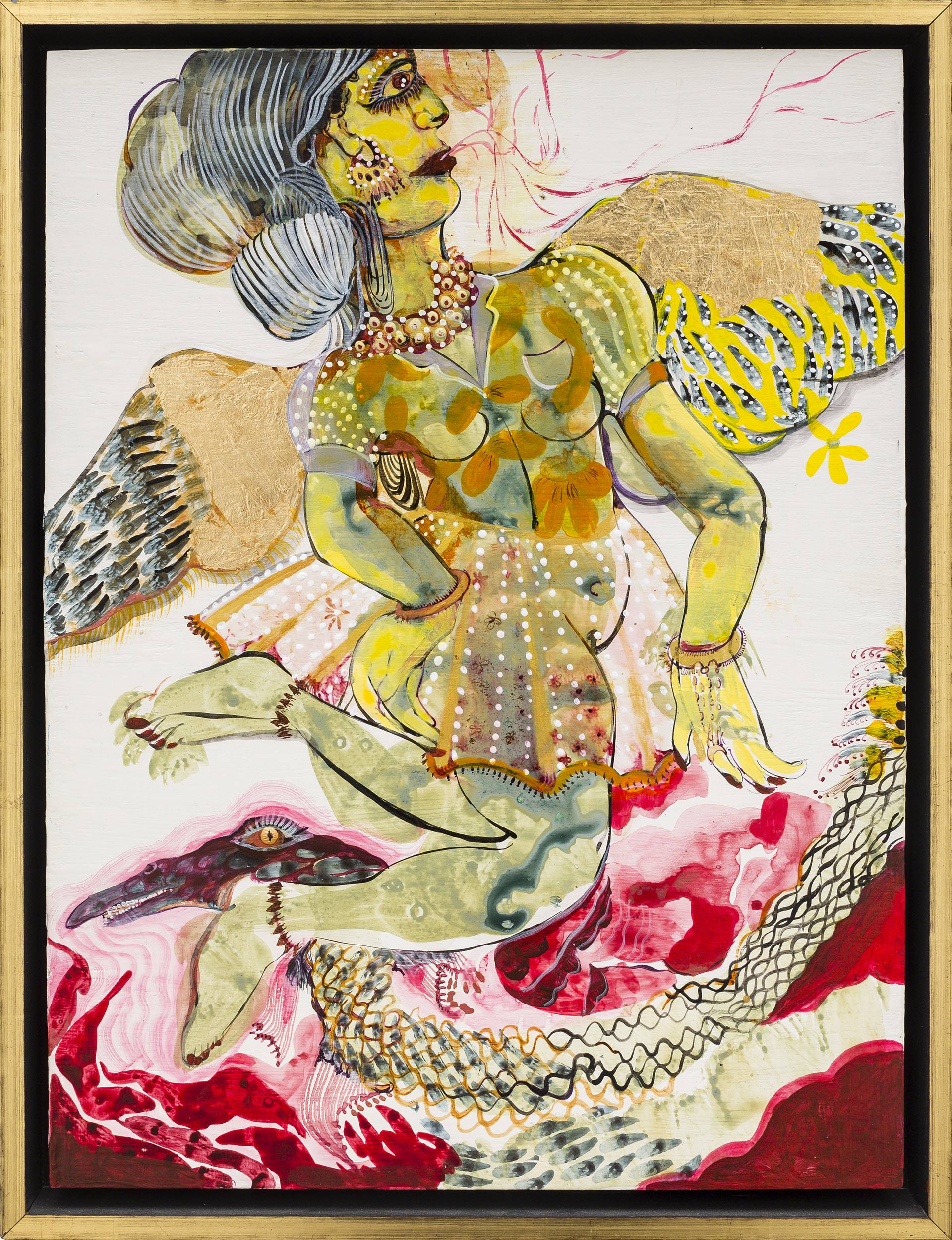

Art in Focus: Women From the Center is comprised of four themes: “Women and Institutions” looks at artists who challenge bodies of knowledge and control that have historically marginalized or oppressed women. “Space and Place” showcases women artists who reimagine urban and pastoral environments and imprint their own subjectivity on these spaces. “Women as Muses” challenges traditional understandings of artist and muse—namely that of an active male artist and a passive female muse—for on this wall women play both roles. Finally, “Beyond the Figure” examines the role that women have played in breaking free from the politics of figuration.

Art in Focus is the annual exhibition curated by members of the Center’s Student Guide Program. The exhibition introduces Yale undergraduates to museology by providing them with curatorial experience. Women From the Center was curated by Emma Gray, SY ’21; Sunnie Liu, JE ’21; Annie Roberts, SY ’21; Christina Robertson, SM ’22; and Olivia Thomas, MC ’20. The students were led by Linda Friedlaender, Head of Education; Jennifer Reynolds-Kaye, former Educator, Academic Outreach; and Rachel Stratton, former Postdoctoral Research Associate. The exhibition and accompanying online presentation were generously supported by the Marlene Burston Fund and the Dr. Carolyn M. Kaelin Memorial Fund.